2. The word is a weapon. Literary complicity and internationalist solidarity

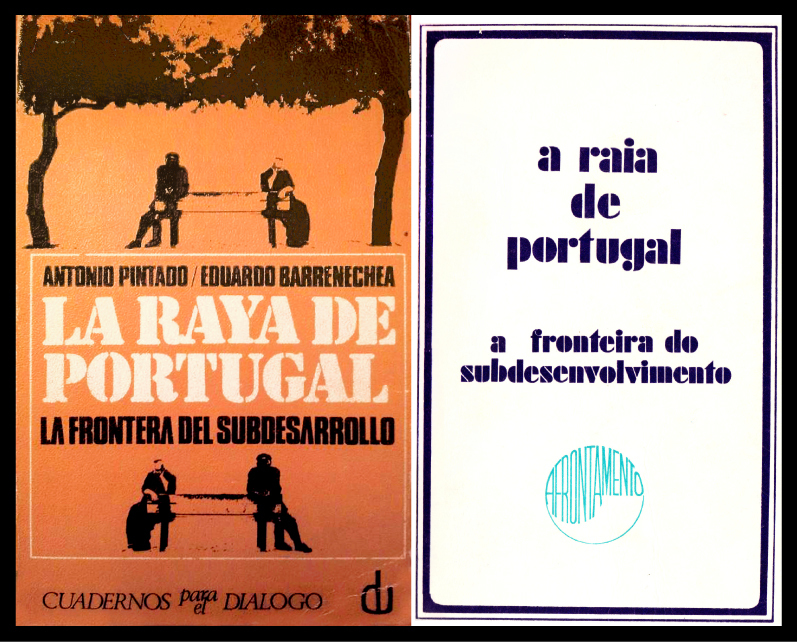

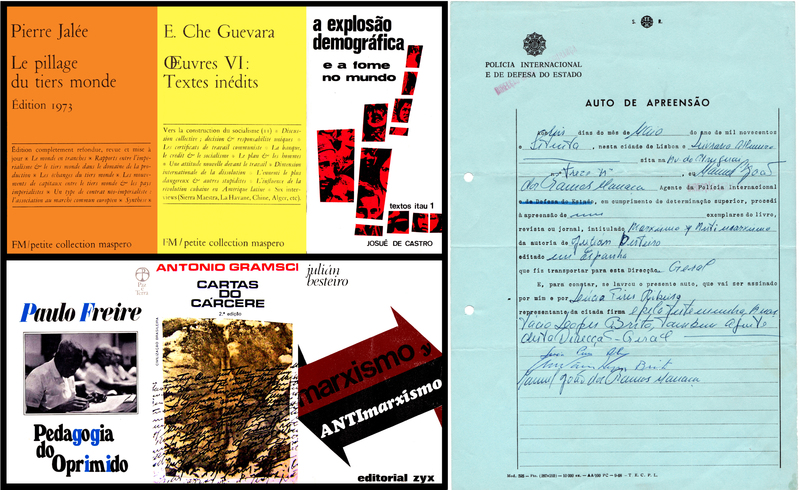

With a bookshop located in the densely populated neighbourhood of Benfica, on the busy Avenida do Uruguai, Ulmeiro began by importing and selling many works by Spanish counterparts, some known for their resistance to Francoism (Aguillar, Ayuso, EDICUSA, Librería Miguel Ibañez, Ruedo Ibérico, Seix Barral, Siglo XXI and Xyz). On the other hand, it left works by Pessoa to Alianza Editorial, encouraging their discovery and translation by familiar people. In order to import political essay it also contacted the publishers Maspero (Paris) and Feltrinelli (Rome) and the Brazilians Martins Fontes and Civilização Brasileira (these ones via intermediaries).

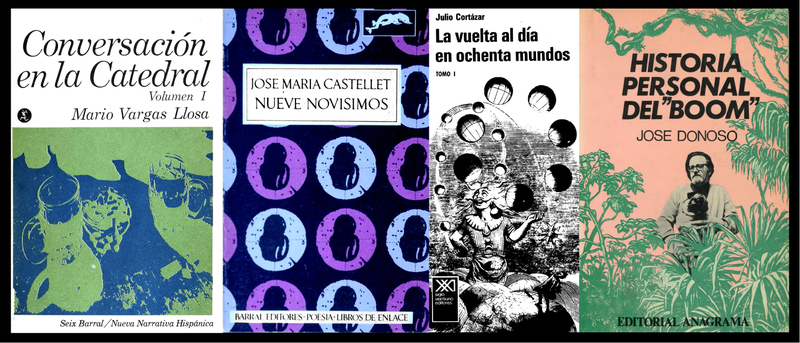

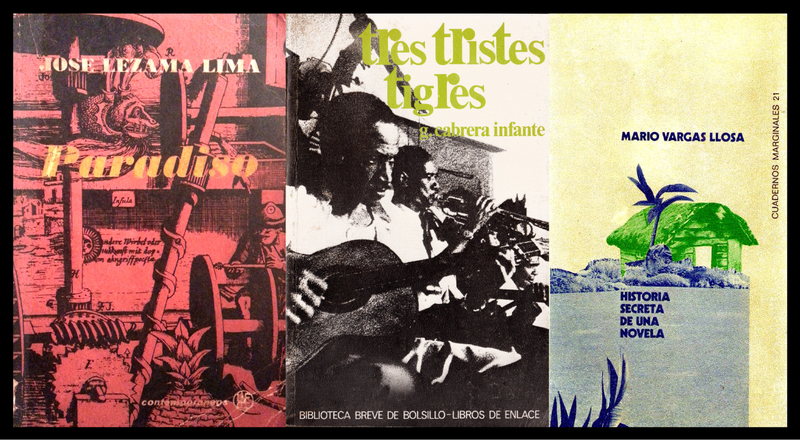

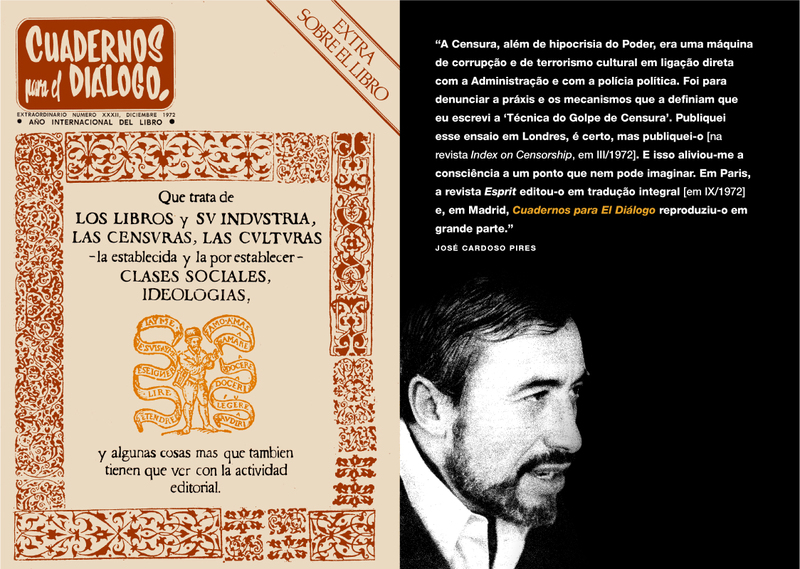

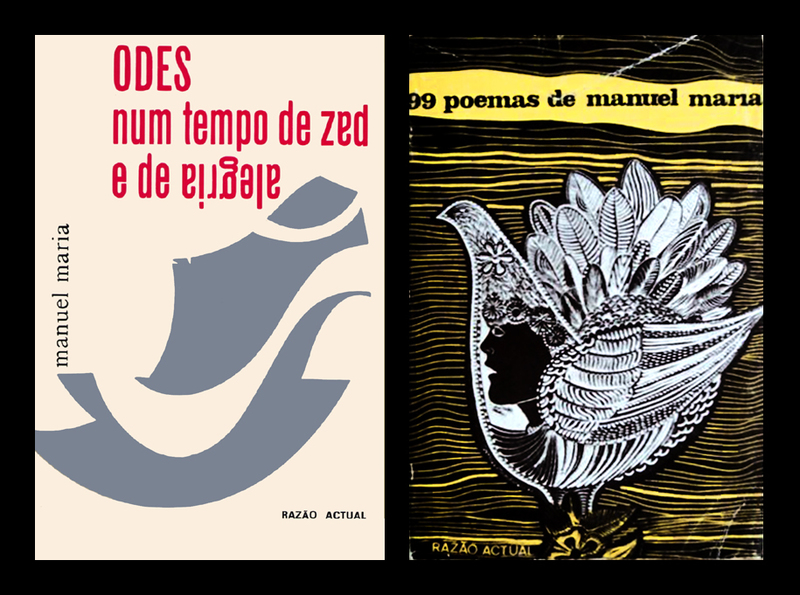

Taking advantage of the great convergence existing in the Iberian protestant youths of the 1960s and 1970s, the dissemination of works and authors also involved participating in other people' activities (such as a celebration-meeting of the Christian democrats of Cuadernos para el Diálogo, in Madrid, 197-) and organising tertulias (gatherings) at the bookshop. In these meetings participated lovers of Spanish language literature such as José Bento and Fernando Assis Pacheco. There were declaimed, debated and sold works by Spanish novelists and the Latin American literary boom (José María Castellet, Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa, etc.), in Castilian and at affordable prices (because they were pocket books), but also the translations integrated in the Cadernos Peninsulares [Peninsular Notebooks] and other Portuguese collections. Of these evenings of poetry and music it is worth mentioning one that had the participation of the Spanish poet Manuel María, who had been at Ulmeiro in January 1972, to present and recite in Galician his poetry, that he had then anthologized, revealing the local social reality. His poems were present in the voice of Benedicto García Villar, guru of Voces Ceibes (a group linked to the protest song, cancion de protesta, and which used Galician as a weapon) and friend of José Afonso, taking part that same year in a tour with him and in his album «Eu vou ser como a toupeira» [«I will be like the mole»] (ed. by Orfeu).

Ulmeiro thus made a special contribution to the dissemination of works associated with progressive thinking and the most innovative creation, originating mainly from Spain, France and Brazil, and helped to reveal authors such as those from the Latin American literary boom and revolutionary theorists (Marxists and Third Worldists) of various currents.

This web publication had the support of CHAM (NOVA FCSH/UAc), through the strategic project sponsored by FCT (UIDB/04666/2020). This work is funded by national funds through the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Norma Transitória – DL 57/2016/CP1453/CT0062.

See next section: 3. The final fight against the dictatorship >>